I have many fond memories of visiting the Mandarin as a child with my extended family for holiday gatherings, and while the food is not top notch quality, who can resist all you can eat sushi, Chinese fare, and desserts! Oh so many desserts. My mom and I would always go overboard at the salad bar, and my dad and I would get plates full of only crab legs. Mostly, going to the Mandarin was a fun filled excuse to pig out, but if it had never been for a woman by the name of Joyce Chen, the Chinese buffet as we know it may have never been born.

Joyce Chen was born in Beijing in 1917 and is credited for bringing Northern-style Chinese cuisine to the West. Before immigrating to Cambridge, Massachusetts and opening her first restaurant in 1958, most of what was considered Chinese food in North America centred around egg foo yung and chop suey. At this time, Chinese take-out always came with bread instead of rice, due to the cultural influence of the Irish and Italian immigrants that resided in Boston and Cambridge at this time. Chen’s restaurant (aptly named “Joyce Chen Restaurant”) changed all of that. She introduced different styles of Chinese food that were authentic to where Chen grew up, and that Americans had never seen before, such as: Peking Duck, Moo Shi Pork, Scallion Pancake, and Hot and Sour Soup.

The dish that she is most known for sharing was “guo tie”, or what we would know as pot stickers. Back in 1958, diners had never seen this style of dumpling before, and Chen was afraid that her customers would confuse go tie with the heavy dough like dumplings of the South. She wanted to convey the meaty filling aspect of the dish, so she borrowed from Italian culture and named them “Peking ravioli”. The description of these Peking ravioli from Chen’s debut menu reads as follows: “Delicious Cresents — stuffed with meat and vegetables, served pan-fried, boiled, or steamed.” The name proved to be so popular that many Chinese restaurants in and around Massachusetts continue to call their pot stickers Peking ravioli to this day. In order to increase business at her restaurants during the slower nights of the week, Chen introduced a buffet to her customers of authentic Chinese food. In order to promote unusual styles of food to patrons who may fear commiting to the unknown, Chen offered unique dishes to the buffet that were not offered on the menu.

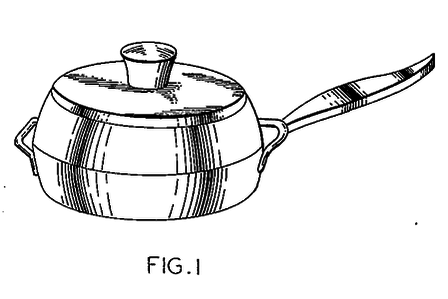

Not only did Joyce Chen revolutionize people’s conception of Chinese food, but she also changed the way we cook it through the patented invention of the flat-bottom wok.

Her enterprise extended to running four restaurants, teaching cooking classes, creating a full line of Chinese cooking utensils, producing a line of bottled condiments and sauces, writing and self publishing a cookbook, and even staring in her own PBS cooking show called Joyce Chen Cooks. According to celebrity chef Ming Tsai, Joyce Chen is

“the Chinese Julia Child […] Joyce Chen helped elevate what Chinese food was about. She didn’t dumb it down. She opened people’s eyes to what good Chinese could taste like.”

In fact, her cooking show was even filmed on the same set as Julia Child’s first program, The French Chef.

Among her many accomplishments, Joyce Chen was also a healthy eating activist, as she refused to use Red Dye #2 or any other food colouring in her restaurant dishes. Her cookbook’s recipes did not include any MSG, and even had a forward by heart surgeon Dr. Paul Dudley White who promoted her book as being heart friendly, low in fat, and high in nutritional quality.

Her son Stephan Chen continues his mother’s legacy as the president of Joyce Chen Foods and the sales of her sauces, oils, spice blends, and frozen Peking ravioli through supermarkets in the United states. In 2014, the United States Postal Service included her in its “Celebrity Chefs Forever” series, commemorating chefs that revolutionized cuisine in the U.S., including Julia Child, James Beard, Edna Lewis, and Felipe Rojas-Lombari. Joyce Chen was not only a great chef, restaurateur, and entrepreneur, but also a creative innovator who shared her love of Chinese culture with all of North America.

References:

http://luckypeach.com/the-story-of-peking-ravioli/